HELPING THE CHILDREN OF SREBRENICA

Helping the Children of Srebrenica

World Life Trust aims to heal hearts of refugee youths

By: Asad Yawar (AlexYawar)

July 1995: one of the worst moments in the history of modern Europe unfolds. The United Nations-declared "safe area" of Srebrenica is effectively handed over to advancing Bosnian Serb forces by the Dutch UN contingent entrusted with defending its civilian population.

July 1995: one of the worst moments in the history of modern Europe unfolds. The United Nations-declared "safe area" of Srebrenica is effectively handed over to advancing Bosnian Serb forces by the Dutch UN contingent entrusted with defending its civilian population.

The result is the continent's worst massacre since the end of the Second World War. At least 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men - possibly many more - are killed by the Bosnian Serb army, while the women are singled out for rape, and then death. Incredibly, the leader of the Dutch contingent then goes on to drink a toast with general Ratko Mladic, who is in charge of the Bosnian Serb army attacking Srebrenica.

In May 2006, Srebrenica is a long way from most people's minds. Slobodan Milosevic, whom most commentators agree was the principal mover behind the carnage in the former Yugoslavia, is dead, Ratko Mladic is an indicted war criminal, and peace and some semblance of stability have returned to the region.

But the scars from Srebrenica are still much in evidence amongst those who survived the ordeal. Many of those who lived through Srebrenica were children who are now reaching their late teens. For most of them, prospects of a normal life, including having a job in their native country of Bosnia-Herzegovina, are slim; partaking in the opportunities offered by the dream of European Union membership is even more distant.

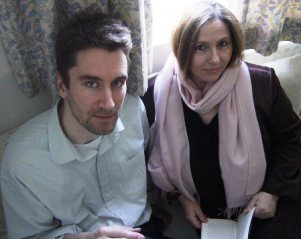

But for Anglo-German couple Fiona and Frank Klimaschewski, Srebrenica is still very much a live issue. Their organisation, the World Life Trust (www.worldlifetrust.org), which is in the final stages of securing full charitable status in the UK, is dedicated to helping the survivors of Srebrenica - notably, those who lost one or more parents in the bloodshed - through organising intercultural exchange programs with youths of similar age from London. World Life Trust's newest venture along these lines, called PEACE (Peer Education And Cultural Exchange) for East West European Youth, has secured funding from the British Council.

OhMyNews caught up with the Klimaschewskis at their home in London's eternally trendy Notting Hill, where we talked about the work of the World Life Trust, the current situation in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and with some trepidation, this summer's World Cup finals in Germany.

OhmyNews: Bosnia-Herzegovina has been at peace for over ten years now, and the country has started to attract major investment from the likes of Coca-Cola and Siemens. Has this impacted on the lives of the children that you work with, and do they feel more hope than they did a few years ago?

Fiona Klimaschewski: Well, the last time I saw them was in January of last year, and I would say that over the last five years, there's predominantly been no change in any of their situations. One or two have relatives living abroad in places like Germany, and one family for instance have had a new house built by the brother from income made in Germany. One or two got rehoused in slightly better housing on a rebuilding project in central Tuzla.

But two-thirds of the children come from outlying areas (of Tuzla). Two of the children come from refugee camps, and there's been absolutely no change in their circumstances, and I would say that it's actually more hopeless than it was, because after the war there was a hope that things would get better, but so long after the war, when things didn't get better for them, I think it's a more hopeless situation.

The teacher project leader, who lives in Tuzla, her job security is much the same; her income is much the same, and she still feels that in order to give her children a chance, she has to leave Bosnia. Most of the children - teenagers they are now, fifteen to seventeen years old - feel that they still need to think in terms of going to another country in order to attain a good standard of living.

Frank Klimaschewski: I think the fact that the children are very keen to come (to England for the program) shows that they are desperate for a change, and that they can be very active themselves once they are given an opportunity, and these opportunities seem to have been lacking so far. Foreign aid has not provided enough opportunities for involving themselves in something constructive.

OhmyNews: As survivors of Srebrenica, the children you work with must be suffering from tremendous psychological trauma. Does this make them harder to work with?

Fiona Klimaschewski: I think on the whole that these particular teenagers that we've been working with since 1998, that they're very courageous. Very few of them are psychologically traumatised in a recognisable way. They obviously carry a sadness; they carry a heavy responsibility, usually and especially the boys. It's particularly noticeable with those that are only children: sometimes they are the only emotional support to their mothers who've lost everyone else. So in that sense they have a great burden on their shoulders.

Some of them are the main emotional support for their family, because it was a patriarchal society where the men generally lead. So a lot of the women are very confused and lacking in direction, having lost their husbands, their brothers, their fathers, their sons. But on the whole I'd say that the children were actually surprisingly healthy. That's the most remarkable thing: that they are very grounded, realistic, hard-working, responsible, amazing teenagers. And that's what makes them such a joy to work with. They're not spoilt by consumerism or materialism. They're grateful; they're on the whole clever...they're a real joy to work with.

Some of them are the main emotional support for their family, because it was a patriarchal society where the men generally lead. So a lot of the women are very confused and lacking in direction, having lost their husbands, their brothers, their fathers, their sons. But on the whole I'd say that the children were actually surprisingly healthy. That's the most remarkable thing: that they are very grounded, realistic, hard-working, responsible, amazing teenagers. And that's what makes them such a joy to work with. They're not spoilt by consumerism or materialism. They're grateful; they're on the whole clever...they're a real joy to work with.

OhmyNews: Just over ten years ago, Bosnia-Herzegovina was a country split into three. Now the country is rapidly centralising, with one currency, one united football league, one police force and even one army. Do the refugee children feel hopeful about the future for a united and reconciled Bosnia-Herzegovina?

Fiona Klimaschewski: It's difficult to tell. They tend to shy away from talking about politics of any kind. They don't want to talk about religion, they don't want to talk about politics; they are very, very reticent to give you their views. So I'd say on the whole that they keep fairly quiet; that's a fairly consistent thing with them.

I haven't talked specifically with them about these questions but I just know that in general they want to...they tend to avoid direct questions and direct answers about religious and political issues.

Frank Klimaschewski: I think that this is just a sore topic with lots of associated disappointment. And it seems that they don't like to speculate and throw themselves into false hopes. And from what I hear, and from what I know, I can understand why.

Fiona Klimaschewski: One of the things that was happening that affects them very badly was that at one point, the widows' pensions were not being paid consistently to their mothers. Sometimes, this is the only income that the women have, and they might be keeping three or four children on that widows' pension, and if it doesn't turn up - if it's delayed for administrative reasons - that is really a potential existential crisis as to how they're going to survive.

A lot of the women were also not trained (professionally or vocationally) and there is not much job training available. A lot of these women were expecting to be housewives. They're great at making clothes, cooking and basically keeping house whilst the men go out to work, and that's what they were expecting to do in their lives. And not all of them - in fact, very few of the mothers are trained. And for that reason, they end up being absolutely, totally dependent on these widows' pensions which have, as I say, been inconsistent...

Frank Klimaschewski: ...which (amounts to) borderline abuse. That may be a bit harshly formulated, but the official side, the local government, is acting irresponsibly, and it raises some kind of suspicion, too, as to where their interests lie...

OhmyNews: So much has happened since the end of the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1995. We've had the war between Serbia and NATO in Kosovo, we've had 9/11, we've had military conflict in Afghanistan and now Iraq. Is the world in danger of forgetting about Bosnia?

Fiona Klimaschewski: Yes. I think in general, people do find it hard to relate to the Bosnian teenagers because they're not in a...(or rather) they appear not to be in a life-threatening situation, but indeed some of them are. It's just a different kind of threat: the threat of hopelessness, and despair, and depression, and (the feeling of there being) no future, especially for those that are in some of the smaller, outlying areas of the smaller towns.

One teacher was (recently) telling me that her weekly wage is (the value of) a London Underground weekly travel ticket. Wages have not risen that much (since the end of the war).

Frank Klimaschewski: Europe might be missing its chance to really clean up its backyard, and it lacks the will to face the legacy that it will have for the future.

OhmyNews: What is the best thing about working with these children?

Fiona Klimaschewski: That no matter how much you put into it, you always get more out of it. In terms of relationships, the relationships with them are very trusting. They put a lot of trust in us, and they put a lot of faith in us, and we kind of represent a hope to them. They're very grateful, and we hope that some of these teenagers will form teams that will work with and train other teenagers in cultural diversity workshops.

Frank Klimaschewski: It's a grassroots feel, it's a grassroots approach, I think, towards a form of practical integration in an underdeveloped European region.

Fiona Klimaschewski: It's also amazing to see that young people who have had every conceivable trauma thrown at them - lost male members of the family, landed up in refugee camps with basically nothing, with very few resources, tend to be A-grade students, working really hard and still giving it their all. They're incredibly rewarding to work for. They're very loving, they're very open, very pure-hearted teenagers.

And they're quite an amazing contrast to a lot of the young people who are, say, in central London, a city that has everything, where people will have everything and yet are spiritually impoverished. The Srebrenica children are impoverished in a monetary, economic sense but they're not impoverished spiritually. And that's the other reason it's so incredible to work with these teenagers, that...the whole experience is just an unfolding of amazing knowledge.

OhmyNews: What kind of things does your organisation need donations for?

Fiona Klimaschewski: The British Council funding that we have has taken care of all the basic needs like flights, accommodation and basic travel costs for our first project (London, July 21-31, 2006). So donations from now on would essentially be used to do some slightly more ambitious things with them. For example, we wanted to give them opportunities to photograph and record their own visits, make up journals. We wanted to do some slightly different things with them: maybe take them to Oxford, let them see another city outside of London.

We also want to take them on a tour of London, and just show them the diversity of the city, from Canary Wharf to Green Park; from Buckingham Palace to Shepherd's Bush. To show them the diversity of one city. Because Tuzla, where most of the teenagers come from, is quite consistent: it doesn't have that kind of variety.

Frank Klimaschewski: Over centuries, Bosnia-Herzegovina has been a model for various cultures to coexist side-by-side, tolerating each other, and this has been forgotten. And we think that these youngsters will see and (re-)discover in London a multi-cultural life that was once outstanding in the Balkans, as well as in the southern part of Europe, like Spain.

The "open society" that we now have lacks a certain awareness. It's in danger of disintegrating because of its materialistic focus. Whereas in the Balkans, the focus was definitely based on understanding, evaluating, tolerating: a very practical way of coexisting and sharing. And I think these children need to teach us this very simple way of living that can still be experienced in the Balkans today.

Fiona Klimaschewski: Sarajevo was in the past an example of strong identities, strong cultural identities living side-by-side and relating to each other. And there's something to be said for that: that identity is not a disease and (different) national identities can coexist and people can coexist with diversity, and we don't have to get rid of all the differences in order to lead good lives, lives where there is respect and recognition and where diversity is not a bad thing.

One of the things that's happening with this project is that the London youth (co-hosting the Srebrenica teenagers) are aged between sixteen and twenty-two. They are from different ethnic minorities and British as well; they're very mixed, they're a very diverse group of London youth, and that's going to be one of the themes of the project, how they will meet each other. A lot of these Bosnians have never met people from Asian cultures. Some of the youth are from Bangladesh, some of the youth are from Pakistan, some of the youth are from the Middle East, some are of white English origin.

So there's quite a lot of diversity within the group and some of the Bosnians will be meeting this kind of diversity for the first time.

It's important for them and all of us to see that problems exist through the actions of human beings, not culture. In other words, intolerance is a phenomenon transcendent of culture: it's not based on you being Bosnian, or Bangladeshi, or anything like that. It's a human problem - not a cultural problem.

OhmyNews: What future projects is your organisation undertaking?

Fiona Klimaschewski: World Life Trust has three projects. One is an orphans' project, which is for much younger children, one is this youth project for teenagers and young adults, and one is a medical project. We have contacts worldwide with various schools, youth organisations etc., and we want this to be an ongoing program that works two or three times a year. We've already located youth in Chechnya, Afghanistan, the Tsunami disaster area, especially Sri Lanka, so we hope to repeat this project maybe once more before the end of this year. But we'd like it to be an ongoing project.

Also the international youth project will hopefully train a team: we're hoping that some of the Bosnians from this program and some of the English youth from this program will get together and form a team that goes on to work in Bosnia-Herzegovina with this multi-cultural diversity workshop program. And maybe working in other parts of Europe, we'd like to involve maybe youth from Germany, from France, from different European countries - and this trend is something that the British Council are promoting - and finding other organisations that we can work with.

The orphan project is a different type of project. It involves much younger children, aged seven to twelve; the oldest is twelve years old. And those are orphans, all of having lost one or both parents in war or disaster. And those orphans, we hope to bring to London and possibly a centre in Europe. We're trying to build a centre in Europe to accommodate those orphans and invite people to act as host families and keep the orphans for a period in the summer where they will have medical attention and a lot of care and recovery and rehabilitation from what they've been through.

We're hoping to do that next year. We're hoping to have the first orphans, approximately ten orphans from various countries next year for a summer program, and we're looking for funds for that too.

Frank Klimaschewski: Project number three is the medical project. It's in accordance with our organisation's overall aim to conduct, procure or commission research programs that relate to relief of distress and hardship, and promote the quality of life in any country. We are looking into the health effects of environmental pollution, as well as strategies for civil protection. We hope to contribute towards greater transparency with regards to subjects like radiation contamination, and possibly CBRN emergency preparedness strategies for urban civilisations in particular.

Fiona Klimaschewski: So of the three projects, the donations are basically to continue the youth programs with different countries, maybe slightly bigger programs; the orphans project, which is bringing orphans to London, Europe for a rehabilitation program; and the medical project which is basically to fund scientific research and fund the attending of conferences and to publish that research.

OhmyNews: This is a project with a lot of implications for conflict areas in other parts of the world. Would you say it has relevance for the problems between North Korea and South Korea? Do you think that a similar kind of program would meet with success there, and in this respect, is your project a model?

Fiona Klimaschewski: I think it can be, definitely. Especially the multicultural diversity theme of these workshops can only be developed and expanded on. And it could very well become a model for any situation where there's been separation and division and conflict. Conflict resolution is part of the workshop program.

OhmyNews: Finally, you're that rarest of things, an Anglo-German couple. The World Cup finals are being held this summer in Germany. Will there be any disputes in the Klimaschewski household if England meet Germany?

Fiona Klimaschewski: We don't have a television! (Laughs.) So as an act of generosity, I don't mind if Germany win!

Frank Klimaschewski: I am absolutely open for any outcome. (Laughs.) And I will not hold it against my wife (if England win). But I think we will be busy with other things. (Laughs.) Mostly with the youth that are going to come. But they may bind us to watching the live games.

Fiona Klimaschewski: It happens to be the World Cup the week that the youth are here, so we might have to...

Frank Klimaschewski: ...submit to the youths' ambitions!

World Life Trust aims to heal hearts of refugee youths

By: Asad Yawar (AlexYawar)

July 1995: one of the worst moments in the history of modern Europe unfolds. The United Nations-declared "safe area" of Srebrenica is effectively handed over to advancing Bosnian Serb forces by the Dutch UN contingent entrusted with defending its civilian population.

July 1995: one of the worst moments in the history of modern Europe unfolds. The United Nations-declared "safe area" of Srebrenica is effectively handed over to advancing Bosnian Serb forces by the Dutch UN contingent entrusted with defending its civilian population.The result is the continent's worst massacre since the end of the Second World War. At least 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men - possibly many more - are killed by the Bosnian Serb army, while the women are singled out for rape, and then death. Incredibly, the leader of the Dutch contingent then goes on to drink a toast with general Ratko Mladic, who is in charge of the Bosnian Serb army attacking Srebrenica.

In May 2006, Srebrenica is a long way from most people's minds. Slobodan Milosevic, whom most commentators agree was the principal mover behind the carnage in the former Yugoslavia, is dead, Ratko Mladic is an indicted war criminal, and peace and some semblance of stability have returned to the region.

But the scars from Srebrenica are still much in evidence amongst those who survived the ordeal. Many of those who lived through Srebrenica were children who are now reaching their late teens. For most of them, prospects of a normal life, including having a job in their native country of Bosnia-Herzegovina, are slim; partaking in the opportunities offered by the dream of European Union membership is even more distant.

But for Anglo-German couple Fiona and Frank Klimaschewski, Srebrenica is still very much a live issue. Their organisation, the World Life Trust (www.worldlifetrust.org), which is in the final stages of securing full charitable status in the UK, is dedicated to helping the survivors of Srebrenica - notably, those who lost one or more parents in the bloodshed - through organising intercultural exchange programs with youths of similar age from London. World Life Trust's newest venture along these lines, called PEACE (Peer Education And Cultural Exchange) for East West European Youth, has secured funding from the British Council.

OhMyNews caught up with the Klimaschewskis at their home in London's eternally trendy Notting Hill, where we talked about the work of the World Life Trust, the current situation in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and with some trepidation, this summer's World Cup finals in Germany.

OhmyNews: Bosnia-Herzegovina has been at peace for over ten years now, and the country has started to attract major investment from the likes of Coca-Cola and Siemens. Has this impacted on the lives of the children that you work with, and do they feel more hope than they did a few years ago?

Fiona Klimaschewski: Well, the last time I saw them was in January of last year, and I would say that over the last five years, there's predominantly been no change in any of their situations. One or two have relatives living abroad in places like Germany, and one family for instance have had a new house built by the brother from income made in Germany. One or two got rehoused in slightly better housing on a rebuilding project in central Tuzla.

But two-thirds of the children come from outlying areas (of Tuzla). Two of the children come from refugee camps, and there's been absolutely no change in their circumstances, and I would say that it's actually more hopeless than it was, because after the war there was a hope that things would get better, but so long after the war, when things didn't get better for them, I think it's a more hopeless situation.

The teacher project leader, who lives in Tuzla, her job security is much the same; her income is much the same, and she still feels that in order to give her children a chance, she has to leave Bosnia. Most of the children - teenagers they are now, fifteen to seventeen years old - feel that they still need to think in terms of going to another country in order to attain a good standard of living.

Frank Klimaschewski: I think the fact that the children are very keen to come (to England for the program) shows that they are desperate for a change, and that they can be very active themselves once they are given an opportunity, and these opportunities seem to have been lacking so far. Foreign aid has not provided enough opportunities for involving themselves in something constructive.

OhmyNews: As survivors of Srebrenica, the children you work with must be suffering from tremendous psychological trauma. Does this make them harder to work with?

Fiona Klimaschewski: I think on the whole that these particular teenagers that we've been working with since 1998, that they're very courageous. Very few of them are psychologically traumatised in a recognisable way. They obviously carry a sadness; they carry a heavy responsibility, usually and especially the boys. It's particularly noticeable with those that are only children: sometimes they are the only emotional support to their mothers who've lost everyone else. So in that sense they have a great burden on their shoulders.

Some of them are the main emotional support for their family, because it was a patriarchal society where the men generally lead. So a lot of the women are very confused and lacking in direction, having lost their husbands, their brothers, their fathers, their sons. But on the whole I'd say that the children were actually surprisingly healthy. That's the most remarkable thing: that they are very grounded, realistic, hard-working, responsible, amazing teenagers. And that's what makes them such a joy to work with. They're not spoilt by consumerism or materialism. They're grateful; they're on the whole clever...they're a real joy to work with.

Some of them are the main emotional support for their family, because it was a patriarchal society where the men generally lead. So a lot of the women are very confused and lacking in direction, having lost their husbands, their brothers, their fathers, their sons. But on the whole I'd say that the children were actually surprisingly healthy. That's the most remarkable thing: that they are very grounded, realistic, hard-working, responsible, amazing teenagers. And that's what makes them such a joy to work with. They're not spoilt by consumerism or materialism. They're grateful; they're on the whole clever...they're a real joy to work with. OhmyNews: Just over ten years ago, Bosnia-Herzegovina was a country split into three. Now the country is rapidly centralising, with one currency, one united football league, one police force and even one army. Do the refugee children feel hopeful about the future for a united and reconciled Bosnia-Herzegovina?

Fiona Klimaschewski: It's difficult to tell. They tend to shy away from talking about politics of any kind. They don't want to talk about religion, they don't want to talk about politics; they are very, very reticent to give you their views. So I'd say on the whole that they keep fairly quiet; that's a fairly consistent thing with them.

I haven't talked specifically with them about these questions but I just know that in general they want to...they tend to avoid direct questions and direct answers about religious and political issues.

Frank Klimaschewski: I think that this is just a sore topic with lots of associated disappointment. And it seems that they don't like to speculate and throw themselves into false hopes. And from what I hear, and from what I know, I can understand why.

Fiona Klimaschewski: One of the things that was happening that affects them very badly was that at one point, the widows' pensions were not being paid consistently to their mothers. Sometimes, this is the only income that the women have, and they might be keeping three or four children on that widows' pension, and if it doesn't turn up - if it's delayed for administrative reasons - that is really a potential existential crisis as to how they're going to survive.

A lot of the women were also not trained (professionally or vocationally) and there is not much job training available. A lot of these women were expecting to be housewives. They're great at making clothes, cooking and basically keeping house whilst the men go out to work, and that's what they were expecting to do in their lives. And not all of them - in fact, very few of the mothers are trained. And for that reason, they end up being absolutely, totally dependent on these widows' pensions which have, as I say, been inconsistent...

Frank Klimaschewski: ...which (amounts to) borderline abuse. That may be a bit harshly formulated, but the official side, the local government, is acting irresponsibly, and it raises some kind of suspicion, too, as to where their interests lie...

OhmyNews: So much has happened since the end of the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1995. We've had the war between Serbia and NATO in Kosovo, we've had 9/11, we've had military conflict in Afghanistan and now Iraq. Is the world in danger of forgetting about Bosnia?

Fiona Klimaschewski: Yes. I think in general, people do find it hard to relate to the Bosnian teenagers because they're not in a...(or rather) they appear not to be in a life-threatening situation, but indeed some of them are. It's just a different kind of threat: the threat of hopelessness, and despair, and depression, and (the feeling of there being) no future, especially for those that are in some of the smaller, outlying areas of the smaller towns.

One teacher was (recently) telling me that her weekly wage is (the value of) a London Underground weekly travel ticket. Wages have not risen that much (since the end of the war).

Frank Klimaschewski: Europe might be missing its chance to really clean up its backyard, and it lacks the will to face the legacy that it will have for the future.

OhmyNews: What is the best thing about working with these children?

Fiona Klimaschewski: That no matter how much you put into it, you always get more out of it. In terms of relationships, the relationships with them are very trusting. They put a lot of trust in us, and they put a lot of faith in us, and we kind of represent a hope to them. They're very grateful, and we hope that some of these teenagers will form teams that will work with and train other teenagers in cultural diversity workshops.

Frank Klimaschewski: It's a grassroots feel, it's a grassroots approach, I think, towards a form of practical integration in an underdeveloped European region.

Fiona Klimaschewski: It's also amazing to see that young people who have had every conceivable trauma thrown at them - lost male members of the family, landed up in refugee camps with basically nothing, with very few resources, tend to be A-grade students, working really hard and still giving it their all. They're incredibly rewarding to work for. They're very loving, they're very open, very pure-hearted teenagers.

And they're quite an amazing contrast to a lot of the young people who are, say, in central London, a city that has everything, where people will have everything and yet are spiritually impoverished. The Srebrenica children are impoverished in a monetary, economic sense but they're not impoverished spiritually. And that's the other reason it's so incredible to work with these teenagers, that...the whole experience is just an unfolding of amazing knowledge.

OhmyNews: What kind of things does your organisation need donations for?

Fiona Klimaschewski: The British Council funding that we have has taken care of all the basic needs like flights, accommodation and basic travel costs for our first project (London, July 21-31, 2006). So donations from now on would essentially be used to do some slightly more ambitious things with them. For example, we wanted to give them opportunities to photograph and record their own visits, make up journals. We wanted to do some slightly different things with them: maybe take them to Oxford, let them see another city outside of London.

We also want to take them on a tour of London, and just show them the diversity of the city, from Canary Wharf to Green Park; from Buckingham Palace to Shepherd's Bush. To show them the diversity of one city. Because Tuzla, where most of the teenagers come from, is quite consistent: it doesn't have that kind of variety.

Frank Klimaschewski: Over centuries, Bosnia-Herzegovina has been a model for various cultures to coexist side-by-side, tolerating each other, and this has been forgotten. And we think that these youngsters will see and (re-)discover in London a multi-cultural life that was once outstanding in the Balkans, as well as in the southern part of Europe, like Spain.

The "open society" that we now have lacks a certain awareness. It's in danger of disintegrating because of its materialistic focus. Whereas in the Balkans, the focus was definitely based on understanding, evaluating, tolerating: a very practical way of coexisting and sharing. And I think these children need to teach us this very simple way of living that can still be experienced in the Balkans today.

Fiona Klimaschewski: Sarajevo was in the past an example of strong identities, strong cultural identities living side-by-side and relating to each other. And there's something to be said for that: that identity is not a disease and (different) national identities can coexist and people can coexist with diversity, and we don't have to get rid of all the differences in order to lead good lives, lives where there is respect and recognition and where diversity is not a bad thing.

One of the things that's happening with this project is that the London youth (co-hosting the Srebrenica teenagers) are aged between sixteen and twenty-two. They are from different ethnic minorities and British as well; they're very mixed, they're a very diverse group of London youth, and that's going to be one of the themes of the project, how they will meet each other. A lot of these Bosnians have never met people from Asian cultures. Some of the youth are from Bangladesh, some of the youth are from Pakistan, some of the youth are from the Middle East, some are of white English origin.

So there's quite a lot of diversity within the group and some of the Bosnians will be meeting this kind of diversity for the first time.

It's important for them and all of us to see that problems exist through the actions of human beings, not culture. In other words, intolerance is a phenomenon transcendent of culture: it's not based on you being Bosnian, or Bangladeshi, or anything like that. It's a human problem - not a cultural problem.

OhmyNews: What future projects is your organisation undertaking?

Fiona Klimaschewski: World Life Trust has three projects. One is an orphans' project, which is for much younger children, one is this youth project for teenagers and young adults, and one is a medical project. We have contacts worldwide with various schools, youth organisations etc., and we want this to be an ongoing program that works two or three times a year. We've already located youth in Chechnya, Afghanistan, the Tsunami disaster area, especially Sri Lanka, so we hope to repeat this project maybe once more before the end of this year. But we'd like it to be an ongoing project.

Also the international youth project will hopefully train a team: we're hoping that some of the Bosnians from this program and some of the English youth from this program will get together and form a team that goes on to work in Bosnia-Herzegovina with this multi-cultural diversity workshop program. And maybe working in other parts of Europe, we'd like to involve maybe youth from Germany, from France, from different European countries - and this trend is something that the British Council are promoting - and finding other organisations that we can work with.

The orphan project is a different type of project. It involves much younger children, aged seven to twelve; the oldest is twelve years old. And those are orphans, all of having lost one or both parents in war or disaster. And those orphans, we hope to bring to London and possibly a centre in Europe. We're trying to build a centre in Europe to accommodate those orphans and invite people to act as host families and keep the orphans for a period in the summer where they will have medical attention and a lot of care and recovery and rehabilitation from what they've been through.

We're hoping to do that next year. We're hoping to have the first orphans, approximately ten orphans from various countries next year for a summer program, and we're looking for funds for that too.

Frank Klimaschewski: Project number three is the medical project. It's in accordance with our organisation's overall aim to conduct, procure or commission research programs that relate to relief of distress and hardship, and promote the quality of life in any country. We are looking into the health effects of environmental pollution, as well as strategies for civil protection. We hope to contribute towards greater transparency with regards to subjects like radiation contamination, and possibly CBRN emergency preparedness strategies for urban civilisations in particular.

Fiona Klimaschewski: So of the three projects, the donations are basically to continue the youth programs with different countries, maybe slightly bigger programs; the orphans project, which is bringing orphans to London, Europe for a rehabilitation program; and the medical project which is basically to fund scientific research and fund the attending of conferences and to publish that research.

OhmyNews: This is a project with a lot of implications for conflict areas in other parts of the world. Would you say it has relevance for the problems between North Korea and South Korea? Do you think that a similar kind of program would meet with success there, and in this respect, is your project a model?

Fiona Klimaschewski: I think it can be, definitely. Especially the multicultural diversity theme of these workshops can only be developed and expanded on. And it could very well become a model for any situation where there's been separation and division and conflict. Conflict resolution is part of the workshop program.

OhmyNews: Finally, you're that rarest of things, an Anglo-German couple. The World Cup finals are being held this summer in Germany. Will there be any disputes in the Klimaschewski household if England meet Germany?

Fiona Klimaschewski: We don't have a television! (Laughs.) So as an act of generosity, I don't mind if Germany win!

Frank Klimaschewski: I am absolutely open for any outcome. (Laughs.) And I will not hold it against my wife (if England win). But I think we will be busy with other things. (Laughs.) Mostly with the youth that are going to come. But they may bind us to watching the live games.

Fiona Klimaschewski: It happens to be the World Cup the week that the youth are here, so we might have to...

Frank Klimaschewski: ...submit to the youths' ambitions!

Source:

http://english.ohmynews.com/ArticleView/article_view.asp?menu=A11100&no=294584&rel_no=1&back_url=

<< Home