OMARSKA CONCENTRATION CAMP

OMARSKA CONCENTRATION CAMP: The Auschwitz no one had imaged

Patti McCracken

We sat at a table near the window overlooking a slim patch of river -- a rather unremarkable river, except in the way it slithered by unnoticed on its way out of town. The air was still, so thick and still, and it was intolerably, menacingly hot on this summer day. My colleague and I downed our coffee, and having finished our breakfast, hung around a bit longer to go through the stack of newspapers in front of us.

We sat at a table near the window overlooking a slim patch of river -- a rather unremarkable river, except in the way it slithered by unnoticed on its way out of town. The air was still, so thick and still, and it was intolerably, menacingly hot on this summer day. My colleague and I downed our coffee, and having finished our breakfast, hung around a bit longer to go through the stack of newspapers in front of us.We were journalism trainers, and the local weekly newspaper in this east Bosnian town had begun a popular series in which a victim of a war crime was profiled each week, including those who had spent time in the nearby Omarska concentration camp. The editor said printing the survivors' accounts was a way for the community to begin to heal, and to document what had happened.

It was our job to critique the stories journalistically: Were they fair? Had facts been verified when possible? How many sources were interviewed? Was the coverage and presentation too sensational?

Despite the oppressive heat, our waiter had restless energy. He kept circling back to us, asking if we needed more juice, more coffee, more water, and then he'd circle back to the counter and eye us from there. I remember him -- his dark thinning hair, his dark eyes, his round face, his compact body. When it was clear we were about to leave, he came back to our table for the last time, tapped his finger on the newspaper's front page photo of a suspected war criminal, and started muttering.

Despite the oppressive heat, our waiter had restless energy. He kept circling back to us, asking if we needed more juice, more coffee, more water, and then he'd circle back to the counter and eye us from there. I remember him -- his dark thinning hair, his dark eyes, his round face, his compact body. When it was clear we were about to leave, he came back to our table for the last time, tapped his finger on the newspaper's front page photo of a suspected war criminal, and started muttering."He says that's a bad man," said my colleague, translating. "He said that man did horrible things to the people here."

The waiter, with his dark brown eyes, crouched down to me, his Bosnian face fronting my American one, pointed to an emptiness in his mouth where some teeth had been beaten out, and said quietly, "Omarska."

And then his brown eyes began to cry.

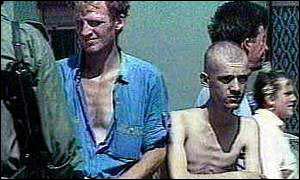

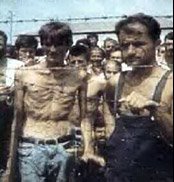

Omarska is the horror that was never supposed to happen again after Auschwitz. It is the oily blackness of soulless madmen who crack their brothers' backs, beat them, starve them down to ghastly skeletons, and worse.

A survivor, Rezak Hukanovic, writes of the torture in his book, "The Tenth Circle of Hell."

"Thirst, hunger, gang rapes, exhaustion, skulls shattered, sexual organs torn out, stomachs ripped open by soldier assassins of Radovan Karadzic."

If the late Slobodan Milosevic was the mastermind of the Bosnian war, Radovan Karadzic was it's premier architect, organizing such camps as Omarska (which he would mockingly label an "investigation center" when reporters came snooping about) to ethnically cleanse a region of its non-Serbs.

If the late Slobodan Milosevic was the mastermind of the Bosnian war, Radovan Karadzic was it's premier architect, organizing such camps as Omarska (which he would mockingly label an "investigation center" when reporters came snooping about) to ethnically cleanse a region of its non-Serbs.In May 1992, intense shelling in and around Omarska forced residents to flee their homes. Upon doing so, many were captured by Serb forces and either killed on the spot or marched off to one of the handful of concentration camps in the area.

The Omarska camp operated for about three months, in which time, the U.S. State Department estimates, up to 5,000 people were killed. Those who were able to return home found their houses occupied by Serbs.

Bosnia has three main ethnic groups, Bosniaks (Bosnian-Muslims), Croats and Serbs, and under Josip Broz Tito's communist regime, ethnicity was essentially a nonissue to the people of Bosnia, as in the rest of Yugoslavia. People married each other, worked together, lived in the same villages and neighborhoods, leaving ethnicity a matter only for the census-takers.

But mighty Milosevic's calls for a Greater Serbia ignited a nationalist flame that shined like a beacon for the likes of Karadzic, who schemed ways to ethnically cleanse vast territories of Bosnia for the purpose of uniting them with Serbia.

This was the third of four wars Milosevic would carry out against his own people, killing hundreds of thousands, and eventually snuffing out the existence of Yugoslavia itself.

Serbs were not the only war criminals to emerge from the Bosnian conflict; Bosniaks and Croats also shoulder blame for shameful acts, a fact many Serbs feel is unjustly overlooked. But it was Milosevic's Serb soldiers who shot like snipers at civilians during the siege of Sarajevo, who killed, execution-style, nearly 8,000 Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica in a matter of hours, and who left us the disturbing legacy of the Omarska concentration camp.

Serbs were not the only war criminals to emerge from the Bosnian conflict; Bosniaks and Croats also shoulder blame for shameful acts, a fact many Serbs feel is unjustly overlooked. But it was Milosevic's Serb soldiers who shot like snipers at civilians during the siege of Sarajevo, who killed, execution-style, nearly 8,000 Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica in a matter of hours, and who left us the disturbing legacy of the Omarska concentration camp.I was in the central city of Tuzla the night a helicopter lifted off from there carrying a captive Milosevic to The Hague. The following morning, I walked around the city -- its once charming main streets now pockmarked by mortar attacks -- and tried to read faces for signs of joy, vindication, relief. The faces gave away nothing, nothing at all, and I thought maybe the war had taken it all from them.

The day his trial started, I sat on a stool in a Bosnian cafe and watched the Bosnians as they stonily watched Milosevic. The country is now divided into two entities, and I was in the Serb-controlled part, waiting to meet a dear friend, a Bosnian-Serb editor who lost both of his legs in a car bomb attack for reporting about war crimes. He had received several death threats before the 3-pound bomb was placed under his car on his birthday, and I asked him once why he risked his life for war criminals.

"The best thing for Serbs here," he told me, "would be to distinguish between war criminals and Serbs as a whole. Not every Serb is a war criminal."

My friend nearly died exposing the crimes, but the most wanted criminal remains free. Most think Karadzic now lives in a mountain cottage in Serbia, with 20 or more footmen to buy his food, his coffee, his wine, his clothes and his beloved books, because he is, after all, a poet.

My friend nearly died exposing the crimes, but the most wanted criminal remains free. Most think Karadzic now lives in a mountain cottage in Serbia, with 20 or more footmen to buy his food, his coffee, his wine, his clothes and his beloved books, because he is, after all, a poet.No one has found him yet. He slithered away unnoticed, swimming with the current of Omarska's river of tears.

<< Home